I was living in San Francisco when I first heard furtive whispers of a plant-based burger that bled beet juice. Fancy bistros were selling them in limited numbers at their restaurant, hand-served by their celebrity chefs, and receiving glowing reviews on food blogs: “It really tastes like meat!”

Now, you can buy one-pound packages of Beyond Beef and Impossible Meat at supermarkets across the country, indistinguishable from their shrink-wrapped bovine counterparts. By all accounts, “alt-meat” took another leap during the pandemic, with sales jumping 264 percent in the first months of the lockdown.

Still, for us purists, the technology is not quite there. My preferred recipe is to make Mexican-style ground faux beef, sauteeing it with copious amounts of cumin, paprika, and chili powder. You can barely tell the difference. For something simple like a hamburger, though, there is no comparison.

An upstart, though, entered the scene in 2018, with the release of Nuggs 1.0. True to their name, Nuggs are an alternative meat chicken nugget company. The beauty of chicken nuggets, of course, is that it doesn’t really matter what’s in them. It’s part of their appeal. Everyone loves chicken nuggets,” founder Ben Pasternak told me, “but I don’t think anyone would say what’s in them is good.”

As a plant-based version, Nuggs can not only create a replica of the chicken nugget of your childhood—they can say it’s healthier. And for Pasternak, that’s just the beginning of the journey. He believes that, just like social media, alternative meat is going to change the world around us, and we’re in the early days. In his mind, Impossible and Beyond are the equivalent of Myspace and Friendster. He’s trying to build Facebook. Naturally, their next product is going to be a hot dog.

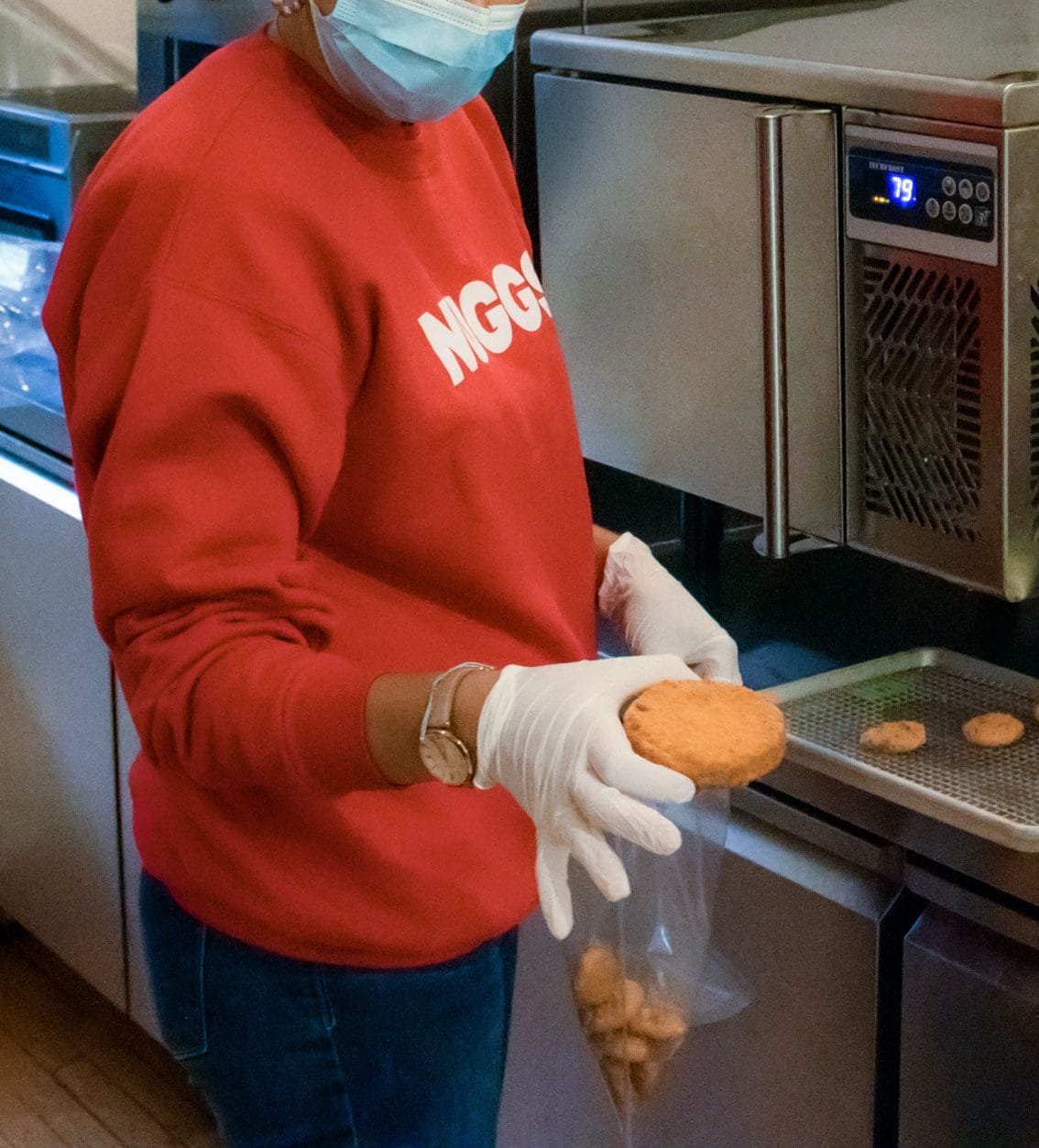

Photos by Leo Schwartz

NEXT-GEN FOOD COMPANY

Improbably—or, perhaps predictably—Pasternak is only 21 years old. He got his start, as he endearingly describes, when he was “younger,” at 14 years old. He was building software when a venture capitalist noticed his work and offered him $500,000 to drop out of school and work on whatever he wanted. Pasternak ended up building a video chat social network called Monkey. It got 20 million users in its first year and was acquired by a competitor.

“I was questioning what I wanted to do with the rest of my life,” he told me. “I had an eighth life crisis.” Climate change interested him, and specifically the twin culprits of transportation and food systems. He saw how much technology had changed technology—from horses to interplanetary rockets in a century—but thought that nutrition was stagnant. “I figured it was an unsexy industry that could be disrupted,” he said.

He saw what Impossible and Beyond were doing and figured he could do it better. They were boring, and beyond the initial stunt campaigns with the burgers, didn’t do much in the way of creative branding. Pasternak grew up on the internet, though, and knew technology through his work on Monkey. He created Simulate, the parent company of Nuggs, to create the next-gen food company.

As a disclaimer, Pasternak is not a cook. His fridge at home is empty—not even a bottle of water. He also didn’t grow up eating chicken nuggets, although he reassured me he eats just about every day now. Even so, he knew that nuggets were the natural first product to “simulate” and break into the market. “They’re very culturally relevant,” he said. “It’s an internet meme type thing.”

Photos by Leo Schwartz

Nuggs have leaned into that cult status. They have provocative artwork—the cover of a box of Nuggs featuring a hand feeding a nugget to a chicken. “There’s not one other plant-based meat company that has a photo of the actual animal they’re simulating,” Pasternak told me. They’re also internet savvy, with organic endorsements from influencers like Bella Hadid. The day I spoke with Pasternak, Karlie Kloss had featured Nuggs on her Instagram.

Despite all the buzz, though, what makes Nuggs unique is the product, not the branding. At first, with the launch of Nuggs 1.0, it was their style that kept people coming back, purely because their general aesthetic looked cool. After almost two years of iteration, though, it’s because they taste so damn good.

The Nuggs office is in Soho, a Manhattan neighborhood more known for boutique clothing shops than food startups. Fittingly, David Byrne (of Talking Heads fame) has a studio in their building. I visited in September, when the streets were unrecognizably empty. Inside the Nuggs office, though, I felt like I was in a laboratory, not a tech company.

"After almost two years of iteration, though, it’s because they taste so damn good."

MORE SCIENCE THAN CULINARY

Of Simulate’s 18 employees, six are food engineers. It’s an aspect of the technology that Pasternak and the team realized would be necessary after spending eight months trying to get them to be the proper level of rubbery. Everything from the crunch of the outer shell to the moistness of the inner meat had to be carefully studied and developed.

They have a verifiable playground to work with: countless gadgets and appliances that I couldn’t even begin to identify. I asked one of the engineers, Bob, whether the process happens in computers as much as the kitchen itself, as he poured over a spreadsheet on his laptop. “100%,” he replied.

When Bob first joined a year ago, he said that people would try out a version and then test it before making a new one. They realized it was inefficient, and started incorporating more and more science and experimentation into the process. Now, they’re building up from the molecular level.

Even so, food is more complex than your average chemical reaction. Simplifying it too much into a series of data could counter-intuitively lose the actual product. “Sometimes it’s better to just eat it and be like, yeah, I like this one better,” said Gabriela, another food engineer on the team. Before Covid, they had regular taste tests at their office with friends and family. Now, much of that has been crowdsourced to the internet.

This is fundamentally what separates food engineers from cooks. “My approach is a lot more science than culinary,” said Gabriela. Right now she’s working on making Nuggs juicier. Where a chef might rely more on instinct, she has to start from the ground floor: defining what “juiciness” actually means, trying out different approaches, and fastidiously documenting everything.

Their work at Simulate resembles the type of molecular gastronomy you might see at legendary restaurants like the now-closed El Bulli in Spain. Coincidentally (or not), Bob trained at the Basque Culinary Center in San Sebastian, and Gabriela at a modern culinary institute in Italy.

Photos by Leo Schwartz

Nuggs might seem like a whimsical first product far divorced from fine dining, but they connect with consumers in a way that fake ground beef never could. Simulate just released a new version—Spicy Nuggs—that sold out in 60 seconds and crashed the website. Days later, they were reselling on eBay for $400.

I was lucky enough to score an order when they got a second batch. They came in a box filled with dry ice and a card on top that read “Welcome to the simulation” in sans-serif block text. I baked them and tried my first one. Crunchy, salty, juicy, peppery—everything you want in a chicken nugget. I felt like a kid again, and promptly ate 15 more.

Related Articles

-

Food & Drink March 16, 2020 | 5 min read Going Rogue in the Kitchen Eventually, I did what most people do when they’re feeling confident in the kitchen. I whipped up a pot of homemade soup without any instructions.

Food & Drink March 16, 2020 | 5 min read Going Rogue in the Kitchen Eventually, I did what most people do when they’re feeling confident in the kitchen. I whipped up a pot of homemade soup without any instructions. -

Food & Drink March 16, 2020 | 6 min read Delicious Differences: Potatoes Mashed potatoes. Fried potatoes. Hash browns. Baked potatoes. The list goes on for all the ways you can prepare potatoes in the kitchen.

Food & Drink March 16, 2020 | 6 min read Delicious Differences: Potatoes Mashed potatoes. Fried potatoes. Hash browns. Baked potatoes. The list goes on for all the ways you can prepare potatoes in the kitchen. -

Food & Drink June 11, 2020 | 6 min read Food Traditions Family traditions don’t always have rhyme or reason, but they give us something to look forward to, and remind us to be grateful.

Food & Drink June 11, 2020 | 6 min read Food Traditions Family traditions don’t always have rhyme or reason, but they give us something to look forward to, and remind us to be grateful.