The first time I came across Indonesian artist Paulus Supomo’s Eat, Sleep, Cook, Repeat poster, I couldn’t get enough of it.

There is something strangely captivating about a poster that looks like it had come straight out of the history books, a simple ink drawing with just enough details to capture the essence of the neat hand-lettered caption, accompanied by a literal translation in Chinese.

Supomo’s posters are mostly in this same format—a cautionary advice or no-nonsense statement in English or Bahasa Indonesia printed in block letters fused with retro aesthetics and a rudimentary Chinese translation that is oftentimes inaccurate and unwittingly humorous.

Unfortunately, I had discovered Supomo’s works a little too late. He had passed away a few months ago in July 2021.

Supomo was a retired factory worker from Bandung in Indonesia’s West Java province who had found his second calling as an artist three years ago.

His son, Yulius Iskandar, tells me, “My father was an introvert and accepted life as it was. He spent his whole life working as a lowly employee after dropping out of school at 14 years old.”

Born in 1955, Supomo was a self-taught artist who never received formal art training. According to Yulius, his hobby of drawing started when he was five years old. Every day, until the end of his life, he never stopped drawing.

In 2017, Supomo gained accidental fame when Yulius put up his work online. In the years after, Supomo eventually achieved cult status in Indonesia where he was particularly popular on social media.

Supomo’s collaborations with local indie brands and experimental musicians such as Gabber Modus Operandi cemented his reputation in Indonesian street culture.

As Yulius explains, Supomo’s illustrations became sought after among young Indonesians “maybe because today’s young people can relate a lot to the quotes.”

“My father was inspired a lot by old school kung fu movies, movie posters, and I really like billboards and signages in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Chinatowns around the world.”

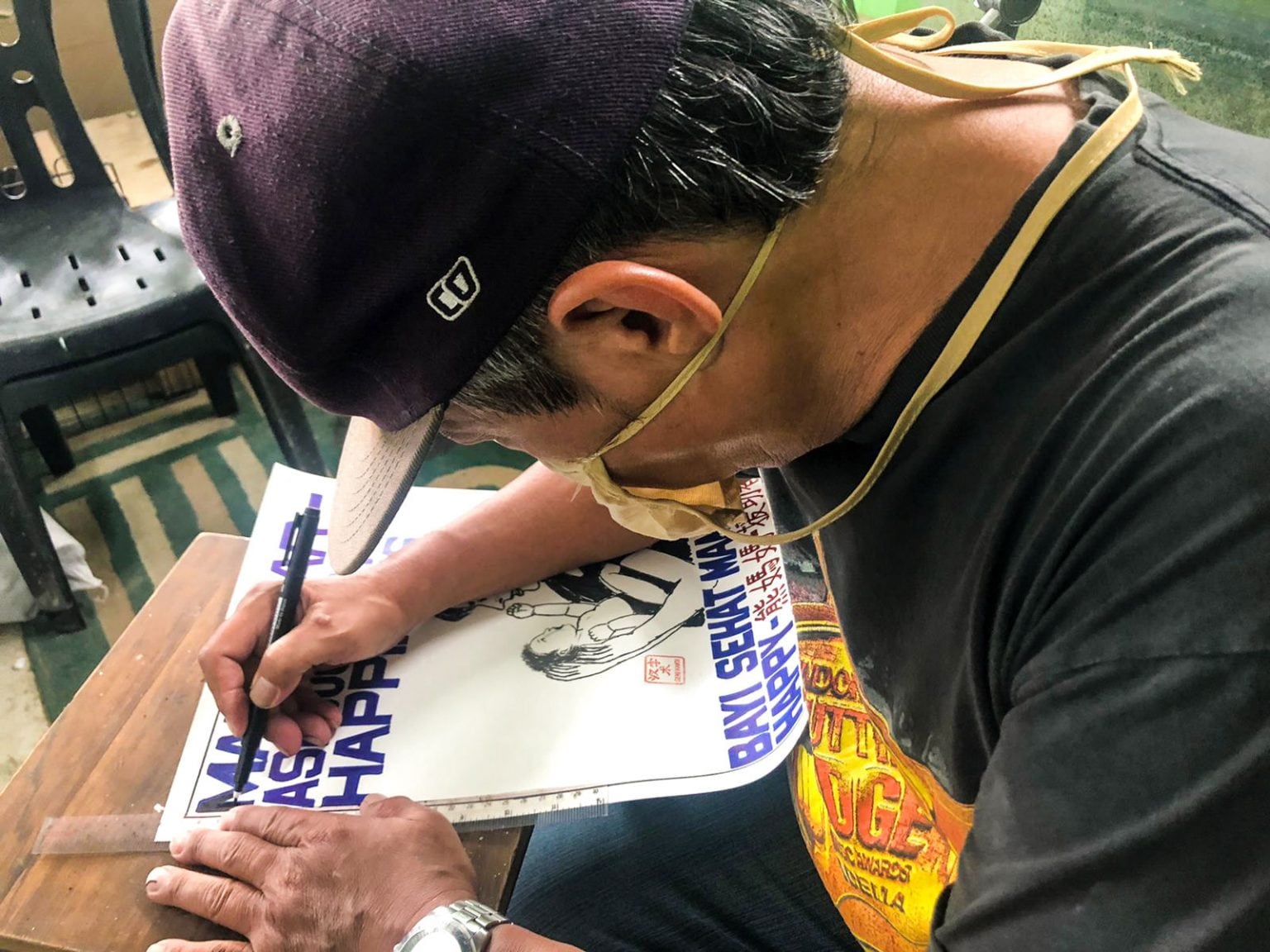

The establishment of their studio, Seni Kanji, which roughly translates into “the art of Chinese characters”, marked the start of a fruitful father-and-son collaboration. Yulius would create the copy while Supomo would illustrate using his trademark blue, black, and red markers, as well as translate the text.

“My father was inspired a lot by old school kung fu movies, movie posters, and I really like billboards and signages in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Chinatowns around the world.”

To me, Supomo’s old-school motivational posters are reminiscent of another genre of retro aesthetics—Ghana’s iconic and vibrant hand-painted barbershop signs and movie posters, but with an Asian spin and sensibility.

Furthermore, behind the light-hearted translations, Supomo’s posters are revealing of a dark period in Indonesia’s history, one marked by the repression and forced assimilation of its ethnic Chinese community.

Under former president Suharto’s decades-long reign, Chinese Indonesians were encouraged to adopt Indonesian-sounding non-Chinese names. Laws also came into force, banning Chinese literature, cultures, and religious expressions including the use of Chinese characters in public spaces.

“Supomo’s posters are revealing of a dark period in Indonesia’s history, one marked by the repression and forced assimilation of its ethnic Chinese community.”

As an Indonesian with origins from Fujian, China, it is not hard to see how Supomo had been exploring his identity through art.

Yulius shares that no one in their extended family could speak Mandarin and Supomo had hoped to preserve his cultural heritage by learning Chinese.

“My father’s Mandarin was not perfect because he had only taken classes for about six months back in 2005, the rest he continued to learn by checking dictionaries and Googling,” Yulius says.

With Supomo’s untimely passing, the onus is now on Yulius to continue his father’s legacy through Seni Kanji. At the same time, he is encouraging his son to draw like his grandfather.

I’m confident that Supomo’s candidly whimsical posters dishing out timeless advice such as Prioritize Breakfast Not Expectations and Good Things Are Coming Down To The Road, Just Don’t Stop Walking will continue to resonate with many people, whether or not they are part of the Chinese diaspora, in the years to come.

Related Articles

-

Home & Design July 27, 2020 | 3 min read Bare Pantry To Full Place: Using Staples We've all been there. After a long day when it's time to go to the kitchen and find something easy to make for dinner, what's there to make? Nothing.

Home & Design July 27, 2020 | 3 min read Bare Pantry To Full Place: Using Staples We've all been there. After a long day when it's time to go to the kitchen and find something easy to make for dinner, what's there to make? Nothing. -

Home & Design October 08, 2020 | 3 min read The Key to a Joyful Kitchen The kitchen is a place that can be overwhelming or inviting, intimidating or a place for creativity to flow freely.

Home & Design October 08, 2020 | 3 min read The Key to a Joyful Kitchen The kitchen is a place that can be overwhelming or inviting, intimidating or a place for creativity to flow freely. -

Home & Design December 22, 2020 | 4 min read From The Earth To The Table Growing up in Malaysia, Lee has always been interested in design. She specializes in small, contemporary stoneware ceramics made with Malaysian clay.

Home & Design December 22, 2020 | 4 min read From The Earth To The Table Growing up in Malaysia, Lee has always been interested in design. She specializes in small, contemporary stoneware ceramics made with Malaysian clay.